Hill Times, August 24, 2020

COVID-19 has shone a spotlight on the cracks in Canada’s social nets, and the fact that they don’t serve Canadians with equity. We now have opportunity to review the structures and policies of Canada and fix some things that aren’t working in the ways we expected. Rip the box open, some might say.

Let’s continue the conversation on changing structures to ensure inclusion and to implement reconciliation for Indigenous peoples, starting with the Norway model. Sāmi make up about 80,000 people across Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Sāmi endured similar negative experiences of colonization based in racism, forced assimilation, sometimes residential schools. Norway, Sweden and Finland each have variations on a truth and reconciliation commission. There is some resistance from Sāmi to the concept of a commission, partly because they reviewed Canada’s experience and noted that our Truth and Reconciliation Commission did not result in structural change.

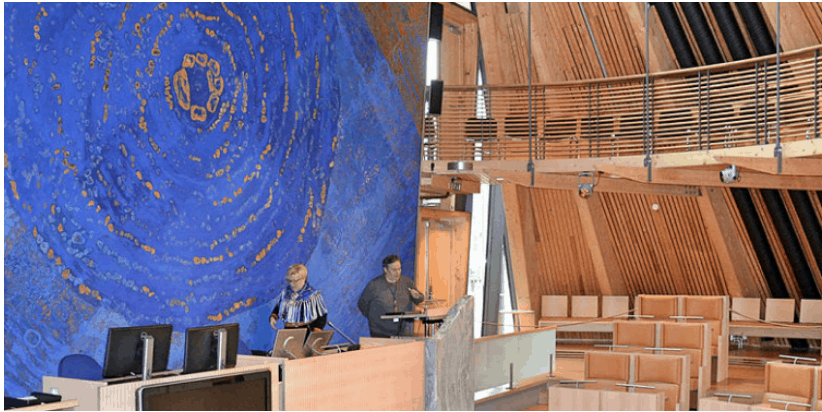

This comes from Sāmi who have their own parliament in Norway. Located in Karasjok, Sāmi hold elections every four years and their elected officials represent Sāmi interests to the Norway federal government. The parliament receives requests from the federal government and can engage on any bill or committee that it chooses. It operates with research and support staff much like any legislature in Canada, and it is fully transparent.

I had the opportunity to tour the Sāmi Parliament and meet elected officials in 2017. I was struck by the grandeur of the building and how its architectural design reflected Sāmi traditional structures. There was a sense of ownership and pride.

There was also some quiet discussion on how to strengthen its influence with the federal government, and some worried that Sāmi voice was advisory only. In some ways the Sāmi have input in their country like Canada’s Indigenous national organizations have input, except that the Sāmi have cohesion and transparency on decisions made. The fragmentation between Canada’s national Indigenous organizations and lack of transparency on how decisions are made hold us back from our full political power in Canada. However the same could be said for Canada: the fragmentation at federal, provincial, and territorial tables and lack of transparency in federal decision-making hold us back from our full potential and inflames a lack of trust.

Would a Sāmi model work better in Canada? If the model had constitutional authority, then yes. Ottawa eats up advisory bodies like beavertails and all that’s left is the crumbs of good intent messing up the floor.

An adaptation on the Sāmi model would be a one-third Indigenous Senate, but with a number of provisos. First, the Senate has to be apolitical because the longhouse of sober second thought was not intended to be a hall of political cronies. Second, Indigenous Senators would be elected by Indigenous peoples. A set number of seats would be for Indigenous Senators; and let’s just do 10-year terms while we’re at it. This would increase the number of young people in Senate, and that seems like a very good thing for diversity.

The point is to increase the voice of Indigenous peoples and embed the principles of reconciliation and pluralism into Canada’s structures. The way to achieving this is through legislation. The result would strengthen Canada as a country. And the hallway and backroom discussions that still hold tinges of racism might be forced to change if there were more Indigenous Senators and more Indigenous MPs. Structural changes are reflected in daily behaviours.

And finally: can we just get on with it and name an Indigenous Governor General next? This would be a great step to overcoming societal inequity and build a more welcoming country, to quote a certain prime minister.